5 Subtance is infinite.

Proof: If substance were not infinite, it would be finite and limited by something. But to be limited by something is to be dependent on it. However, substance cannot be dependent on anything else (premise 1), therefore substance is infinite.

Encapsulated at the start in his Treatise on the Improvement of the Understanding (Tractatus de intellectus emendatione) is the core of Spinoza's ethical philosophy, what he held to be the true and final good. Spinoza held a

relativist's position, that nothing is intrinsically good or bad, except to the extent that it is subjectively perceived to be by the individual. Things are only good or evil in respect that humanity sees it desirable to apply these conceptions to matters. Instead, Spinoza believes in his deterministic universe that, "All things in nature proceed from certain necessity and with the utmost perfection." Therefore, nothing happens by chance in Spinoza's world, and reason does not work in terms of

contingency.

In the universe anything that happens comes from the essential nature of objects, or of God/Nature. According to Spinoza, reality is perfection. If circumstances are seen as unfortunate it is only because of our inadequate conception of reality. While elements of the chain of cause and effect are not beyond the understanding of human reason, our grasp of the infinitely complex whole is limited because of the limits of science to empirically take account of the whole sequence. Spinoza also asserted that sense perception, though practical and useful for rhetoric, is inadequate for discovering universal truth; Spinoza's mathematical and logical approach to metaphysics, and therefore ethics, concluded that emotion is formed from inadequate understanding. His concept of "

conatus" states that human beings' natural inclination is to strive toward preserving an essential being and an assertion that virtue/human power is defined by success in this preservation of being by the guidance of reason as one's central ethical doctrine. According to Spinoza, the highest virtue is the intellectual love or knowledge of God/Nature/Universe.

In the final part of the "

Ethics" his concern with the meaning of "true blessedness" and his unique approach to and explanation of how emotions must be detached from external cause in order to master them presages 20th-century psychological techniques. His concept of three types of knowledge - opinion, reason, intuition - and assertion that intuitive knowledge provides the greatest satisfaction of mind, leads to his proposition that the more we are conscious of ourselves and Nature/Universe, the more perfect and blessed we are (in reality) and that only intuitive knowledge is eternal. His unique contribution to understanding the workings of mind is extraordinary, even during this time of radical philosophical developments, in that his views provide a bridge between religions' mystical past and psychology of the present day.

Given Spinoza's insistence on a completely ordered world where "necessity" reigns,

Good and Evil have no absolute meaning. Human catastrophes, social injustices, etc. are merely apparent. The world as it exists looks imperfect only because of our limited perception.

Pantheism controversy

In 1785,

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi published a condemnation of Spinoza's

pantheism, after

Lessing was thought to have confessed on his deathbed to being a "Spinozist", which was the equivalent in his time of being called an atheist. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because all Nature and God are said to be nothing but extended

substance. This, for Jacobi, was the result of Enlightenment rationalism and it would finally end in absolute

atheism.

Moses Mendelssohn disagreed with Jacobi, saying that there is no actual difference between

theism and pantheism. The entire issue became a major intellectual and religious concern for European civilization at the time, which

Immanuel Kant rejected, as he thought that attempts to conceive of transcendent reality would lead to antinomies (statements that could be proven both right and wrong) in thought.

The attraction of Spinoza's philosophy to late eighteenth-century Europeans was that it provided an alternative to materialism, atheism, and deism. Three of Spinoza's ideas strongly appealed to them:

the unity of all that exists;

the regularity of all that happens; and

the identity of spirit and nature.

Spinoza's "God or Nature" provided a living, natural God, in contrast to the Newtonian mechanical "First Cause" or the dead mechanism of the French "Man Machine."

Philosopher

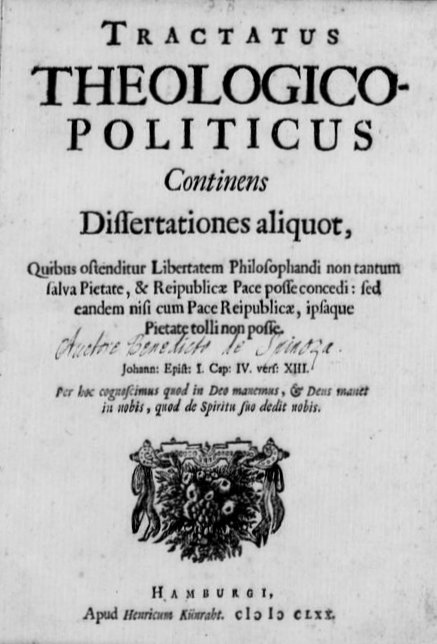

Ludwig Wittgenstein evoked Spinoza with the title (suggested to him by

G. E. Moore) of the English translation of his first definitive philosophical work,

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, an allusion to Spinoza's

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Elsewhere, Wittgenstein deliberately borrowed the expression sub specie aeternitatis from Spinoza (Notebooks, 1914-16, p. 83). The structure of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus does have certain structural affinities with Spinoza's Ethics (though, admittedly, not with the latter's own Tractatus) in erecting complex philosophical arguments upon basic logical assertions and principles. Furthermore, in propositions 6.4311 and 6.45 he alludes to a Spinozian understanding of eternity and interpretation of the religious concept of eternal life, stating that "If by eternity is understood not eternal temporal duration, but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present." (6.4311) "The contemplation of the world sub specie aeterni is its contemplation as a limited whole." (6.45) Furthermore, Wittgenstein's interpretation of religious language, in both his early and later career, may be said to bear a family resemblance to Spinoza's pantheism.

Spinoza has had influence beyond the confines of philosophy. The nineteenth century novelist,

George Eliot, produced her own translation of the Ethics, the first known English translation thereof. The twentieth century novelist,

W. Somerset Maugham, alluded to one of Spinoza's central concepts with the title of his novel,

Of Human Bondage.

Albert Einstein named Spinoza as the philosopher who exerted the most influence on his world view (

Weltanschauung). Spinoza equated God (infinite substance) with Nature, consistent with Einstein's belief in an impersonal deity. In 1929, Einstein was asked in a telegram by

Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein whether he believed in God. Einstein responded by telegram: "I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings."

[1] Spinoza's pantheism has also influenced environmental theory.

Arne Næss, the father of the

deep ecology movement, acknowledged Spinoza as an important inspiration. Moreover, the Argentinian writer

Jorge Luis Borges was greatly influenced by Spinoza's world view. In many of his poems and short stories, Borges makes constant allusions to the philosopher's work, though not necessarily as a partisan of his doctrines, but merely in order to use these for aesthetic purposes--a common tactic in Borges's work.

Spinoza is an important historical figure in the

Netherlands, where his portrait was featured prominently on the Dutch 1000-

guilder banknote,

legal tender until the

euro was introduced in 2002. The highest and most prestigious scientific award of the Netherlands is named the Spinoza prijs (Spinoza prize). Spinoza's work is also mentioned as the favourite reading material for

Bertie Wooster's valet

Jeeves in the

P. G. Wodehouse novels.

See also

Notes

1-

^ Deleuze, 1990.

2-

^ Magnusson, M (ed.), Spinoza, Baruch, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, Chambers 1990,

ISBN 05501604183-

^ Tel Aviv University: "Why Was Baruch De Spinoza Excommunicated?", by Asa Kasher and Shlomo Biderman4-

^ Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy Allen & Unwin (1946) New Ed.1961 p.552

5-

^ Lucas, 1960.

6-

^ Ethics, Pt. I, Prop. V, Proof.

7-

^ Ethics, Pt. IV, Prop. XXXVII, Note I.: "Still I do not deny that beasts feel: what I deny is, that we may not consult our own advantage and use them as we please, treating them in a way which best suits us; for their nature is not like ours...." (Emphasis added to quotation.)

8-

^ Deleuze, 1968.

References

Deleuze, G. (1968) Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Zone Books)

Deleuze, G. (1990) Negotiations trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press)

Lucas, P. G. (1960) "Some Speculative and Critical Philosophers", in I. Levine (ed.), Philosophy (London: Odhams)

Popkin, R. H. (2004) Spinoza (Oxford: One World Publications)

ca. 1660. Korte Verhandeling van God, de mensch en deszelvs welstand (Short Treatise on God, Man and His Well-Being).

[2].

1662. Tractatus de intellectus emendatione (On the Improvement of the Understanding).

Project Gutenberg 1663. Principia philosophiae cartesianae (Principles of Cartesian Philosophy, translated by Samuel Shirley, with an Introduction and Notes by Steven Barbone and Lee Rice, Indianapolis, 1998).

Gallica.

1670. Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (A Theologico-Political Treatise).

[3]

1675/76 Tractatus Politicus (Unfinished)

About Spinoza

Boucher, Wayne I., 1999. Spinoza in English: A Bibliography from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. 2nd edn. Thoemmes Press.

Boucher, Wayne I., ed., 1999. Spinoza: Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century Discussions. 6 vols. Thoemmes Press.

Damásio, António 2003. Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain, Harvest Books,ISBN-13: 978-0156028714

Gilles Deleuze, 1968. Spinoza et le problème de l'expression. Trans. "Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza".

Della Rocca, Michael. 1996. Representation and the Mind-Body Problem in Spinoza. Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-509562-6

Garrett, Don, ed., 1995. The Cambridge Companion to Spinoza. Cambridge Uni. Press.

Gullan-Whur, Margaret, 1998. Within Reason: A Life of Spinoza. Jonathan Cape.

ISBN 0-224-05046-X

Hampshire, Stuart 1951. Spinoza and Spinozism , OUP, 2005 ISBN-13: 978-0199279548

Jonathan Israel, The Radical Enlightenment, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

———, Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670-1752, 2006 (

ISBN 0-19-927922-5 hardback)

Kayser, Rudolf with an introduction by

Albert Einstein. Spinoza: Portrait of a Spiritual Hero. New York: The Philosophical Library, 1946.

Pierre Macherey, 1977. Hegel ou Spinoza, Maspéro (2nd ed. La Découverte, 2004).

———, 1994-98. Introduction à l'Ethique de Spinoza. Paris: PUF.

Matheron, Alexandre, 1969. Individu et communauté chez Spinoza, Paris:

Minuit.

Antonio Negri, 1991. The Savage Anomaly: The Power of Spinoza's Metaphysics and Politics.

———, 2004. Subversive Spinoza: (Un)Contemporary Variations).

Michael Hardt, trans., University of Minnesota Press. Preface, in French, by Gilles Deleuze, available

here.

Pierre-Francois Moreau, 2003, Spinoza et le spinozisme, PUF (Presses Universitaires de France)

Stoltze, Ted and Warren Montag (eds.), The New Spinoza (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Smilevski, Goce. Conversation with SPINOZA. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2006.

Yovel, Yirmiyahu, "Spinoza and Other Heretics", Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989.

Tractus Theologico-Politicus, a name Wittgenstein later paid homage to in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Tractus Theologico-Politicus, a name Wittgenstein later paid homage to in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus