The Seven-Per-Cent Solution is the title of a 1974 novel by Nicholas Meyer. It is written as a pastiche of a Sherlock Holmes adventure, and was adapted for the cinema in 1976. The novel's full title is The Seven-Per-Cent Solution: Being a Reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D..

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution is the title of a 1974 novel by Nicholas Meyer. It is written as a pastiche of a Sherlock Holmes adventure, and was adapted for the cinema in 1976. The novel's full title is The Seven-Per-Cent Solution: Being a Reprint from the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M.D..Published as a "lost manuscript" of the late Dr. John H. Watson, the book recounts Holmes' recovery from cocaine addiction (with the help of Sigmund Freud) and his subsequent prevention of a European war through the unraveling of a sinister kidnapping plot. It was followed by two other Meyer pastiches, in chronological order, The Canary Trainer and The West End Horror, neither of which has been adapted to film.

Plot

Plot

Plot

PlotThe novel begins in 1891, when Holmes first informs Watson of his belief that Professor James Moriarty is a "Napoleon of Crime". The novel presents this view as nothing more than the fevered imagining of Holmes' cocaine-sodden mind; it further states that Moriarty was the childhood mathematics tutor of Sherlock and his brother Mycroft. Moriarty meets Watson, denies that he is a criminal and reluctantly threatens to sue Holmes for slander unless the latter's accusations cease.

The heart of the novel consists of an account of Holmes’ recovery from his addiction. Watson and Holmes’ brother Mycroft induce Holmes to travel to Vienna, where Watson introduces him to Dr. Freud. Using a treatment consisting largely of hypnosis, Freud helps Holmes shake off his addiction and his delusions about Moriarty, but neither he nor Watson can revive Holmes’ dejected spirit.

What finally does the job is a whiff of mystery: one of the doctor's patients is kidnapped and Holmes’ curiosity is sufficiently aroused. The case takes the three men on a breakneck train ride across Austria in pursuit of a foe who is about to launch a war involving all of Europe. Holmes remarks during the denouement that they have succeeded only in postponing such a conflict, not preventing it; Holmes would later become involved in a "European War" in 1914.

One final hypnosis session reveals a key traumatic event in Holmes' childhood. His father murdered his mother and then committed suicide because she had a lover. Moriarty, who broke the news to the young Sherlock, then became a dark and malignant figure in his subconscious (see shooting the messenger). Freud and Watson conclude that Holmes, consciously unable to face the emotional ramifications of this event, has pushed them deep into his unconscious while finding outlets in fighting evil, pursuing justice, and many of his famous eccentricities, including his cocaine habit.

Watson returns to London, but Holmes decides to travel alone for a while, and the famed "Great Hiatus" is thus more or less preserved. It is during these travels that the events of Meyer's sequel The Canary Trainer occur.

References to other works

On the train to Vienna, Holmes and Watson briefly meet Rudolf Rassendyll, the fictional protagonist of the 1894 novel The Prisoner of Zenda, returning from his adventures in Ruritania.

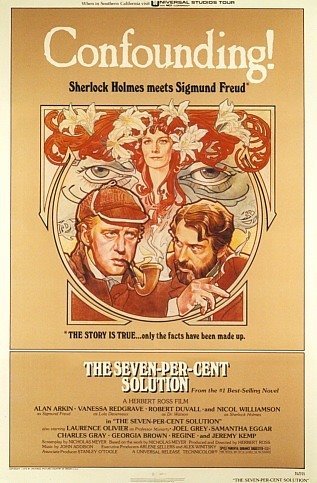

The story was adapted for the screen in 1976, starring Nicol Williamson as Sherlock Holmes, Robert Duvall as Watson, and Alan Arkin as Dr. Sigmund Freud. Laurence Olivier played the brief role of Professor Moriarty.

Though Meyer adapted his novel to screenplay form, the film version differs significantly from the novel, mainly by substituting the book's young Austrian baron-villain with an older, Arabic foe. Also, the film departs from traditional Holmes canon in portraying the detective as light-haired instead of the traditional black-haired, and as a somewhat flirtatious Holmes at that. (Doyle's hero never let women see any signs of interest.) Furthermore, the traumatic revelation that affected Holmes in his childhood is heightened; in the final hypnosis therapy reveals that Sherlock personally witnessed his mother's murder by his father and Moriarity is revealed to have been her lover. Meyer's three Holmes novels are much more faithful to the original stories in these regards. Meyer's adapted screenplay was nevertheless nominated for a 1977 Academy Award.

Charles Gray, who plays Sherlock's brother Mycroft Holmes in the film, later went on to play the same role opposite Jeremy Brett in four episodes of Granada Television's The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes series.

Stephen Sondheim wrote a song for the movie ("The Madame's Song") that was later recorded as "I Never Do Anything Twice" on the Side By Side By Sondheim cast recording.

External links

No comments:

Post a Comment